Basic facts + statistics.

Globally, 1 in 100 deaths is a suicide. 700,000 people die by suicide each year.

A few key things we’ve learned from the research supported by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention:

- Suicide rarely has a single cause. It often emerges when multiple stressors and health challenges combine, leading to feelings of hopelessness and despair.

- Suicide is related to brain functions that affect decision-making and behavioral control, making it difficult for people to find positive solutions.

- 90 percent of people who die by suicide have an underlying—and potentially treatable—mental health condition.

- Depression, bipolar disorder, and substance use are strongly linked to suicidal thinking and behavior.

Access to lethal means appears to be contributing to the current rise in suicide rates. In the United States, over 50% of suicides involve firearms, which are among the most lethal methods. Nearly 90% of suicide attempts involving firearms end in death, in contrast to only 13.5% of attempts involving drug poisonings.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among 14-18-year-olds in the US.

Over the last decade, suicide rates in the US have increased most for people of color in these groups: 43 percent for Black people, 41 percent for Indigenous people, and 27 percent for Latine/Hispanic people.

45 percent of LGBTQ youth seriously considered attempting suicide in the past year. Nearly 1 in 5 transgender and nonbinary youth attempted suicide and LGBTQ youth of color reported higher rates than their white peers.

Myths + Truths

Myth: Suicide is selfish.

Truth: Many people who attempt or die by suicide feel like they are a burden to the people in their lives. Their pain and intrusive thoughts can convince them that the world would be better off without them. In their mind, suicide is the least selfish option because of feeling like a burden.

Myth: You can’t ask someone if they are thinking about suicide.

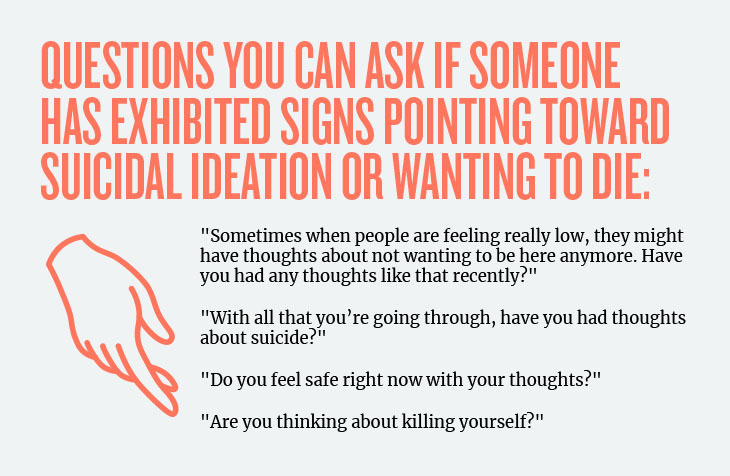

Truth: Asking the question won’t cause someone to suddenly start considering suicide. Instead, it gives them the space to be honest about what they’re experiencing. We want to be thoughtful about how we phrase the question so the person feels safe and not judged. “Are you thinking about suicide?” or “Are you thinking of hurting yourself?” are neutral ways of asking.

Myth: You have to be mentally ill to think about suicide.

Truth: While some mental health diagnoses can be risk factors for suicide, people may consider suicide for entirely different reasons. Other risk factors include trauma, major life changes, family history, and serious physical health conditions.

Myth: Threats of suicide are just for attention.

Truth: When someone shares a truth like this, they’re seeking connection and support. The most compassionate way to react is by listening, letting them know you care about them, and helping them take the next step toward healing.

Myth: Every suicide happens for the same reason.

Truth: Suicide isn’t that simple, which means we have to be willing to listen to the people who have considered or attempted suicide when they tell us why. And then we need to provide support that speaks directly to those reasons.

Myth: Suicide ideation is the same as planning to die by suicide.

Truth: People can experience intrusive thoughts about suicide without ever creating a plan or making an attempt. It's important to be open to asking questions and listening closely so you can respond and offer helpful forms of support.

Myth: I don’t have a role in preventing suicide.

Truth: From the “small” personal connections to the big systemic changes, we can all play a role in suicide prevention. One way to start is by creating space for honest conversations with your people. Share how you’re really doing and be intentional about checking in with them.

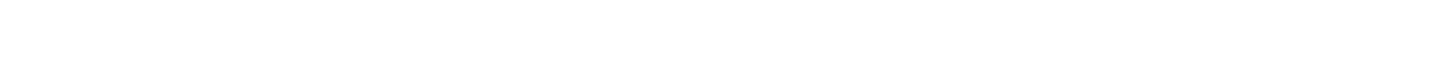

Understanding the signs.

The more we understand about suicide, what keeps people from moving from ideation to action, and what puts people at higher risk, the better equipped we are to support those struggling.

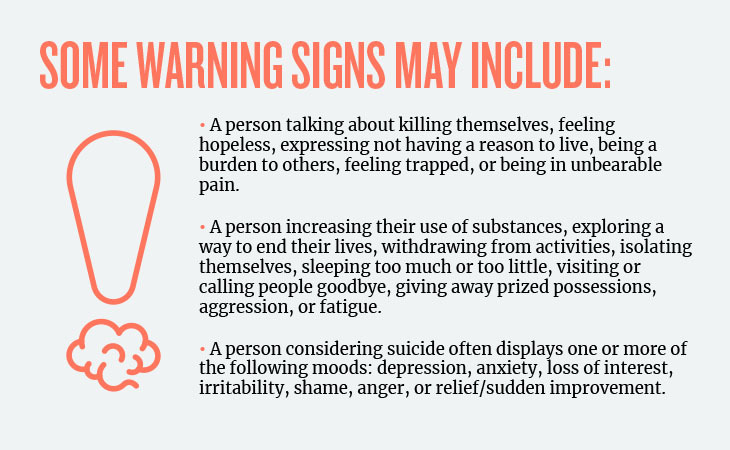

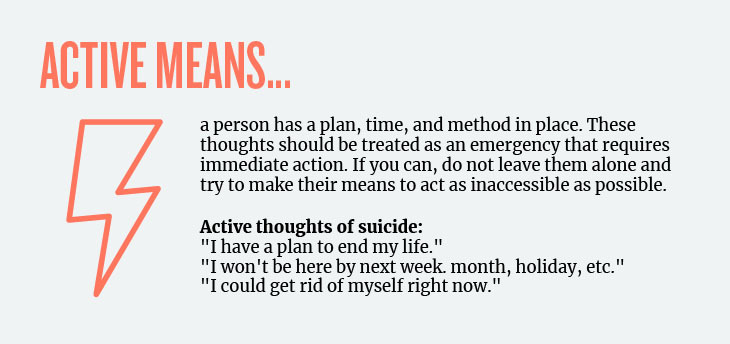

Passive vs. Active

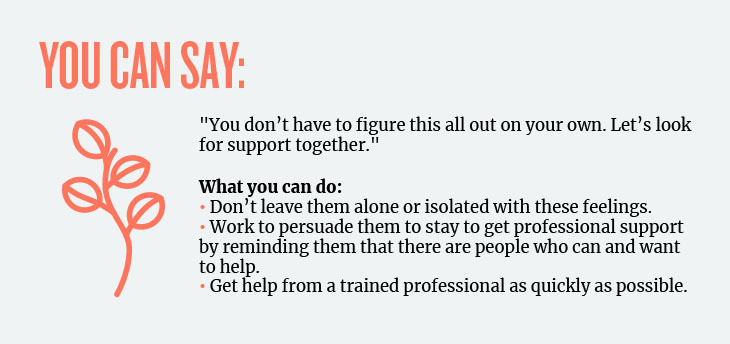

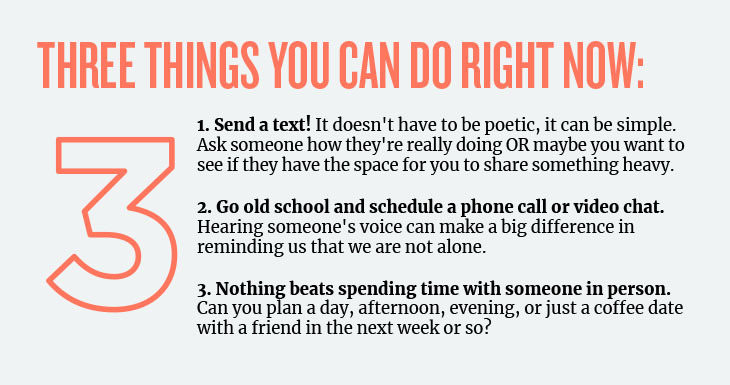

Have the conversation.

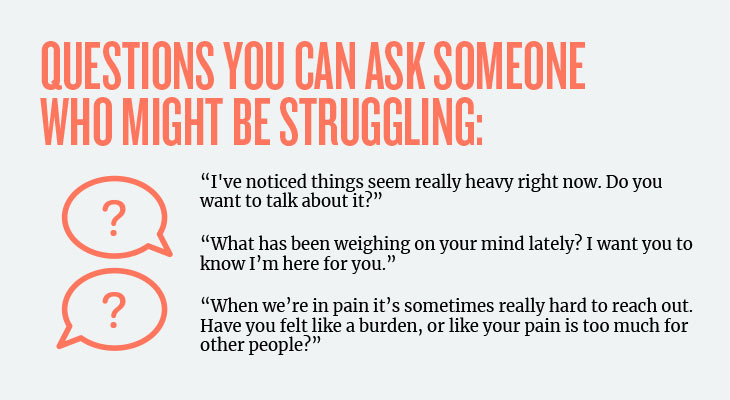

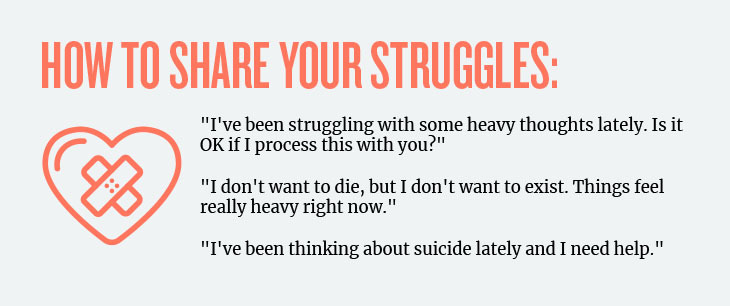

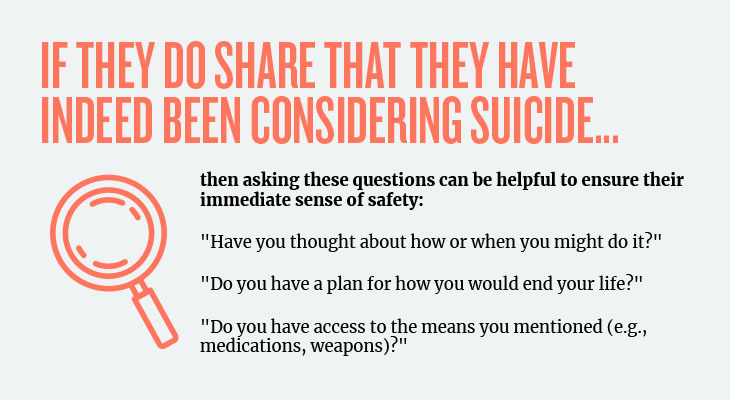

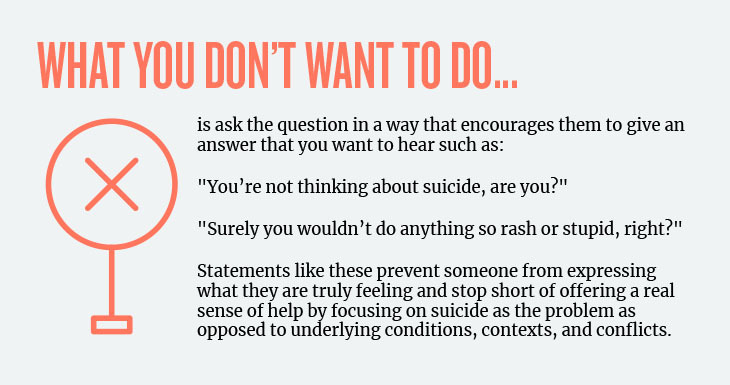

It does not have to be complicated. Checking in with yourself or someone you care about can save a life. If you are concerned about a friend or family member it’s important to ask direct questions, listen carefully, and create the space for them to feel safe enough to be honest.

If they have a plan and a means to act on it, do not leave them alone. Seek immediate help by contacting a mental health professional, crisis hotline, or emergency services here.