This post was originally published on The Emily Program.

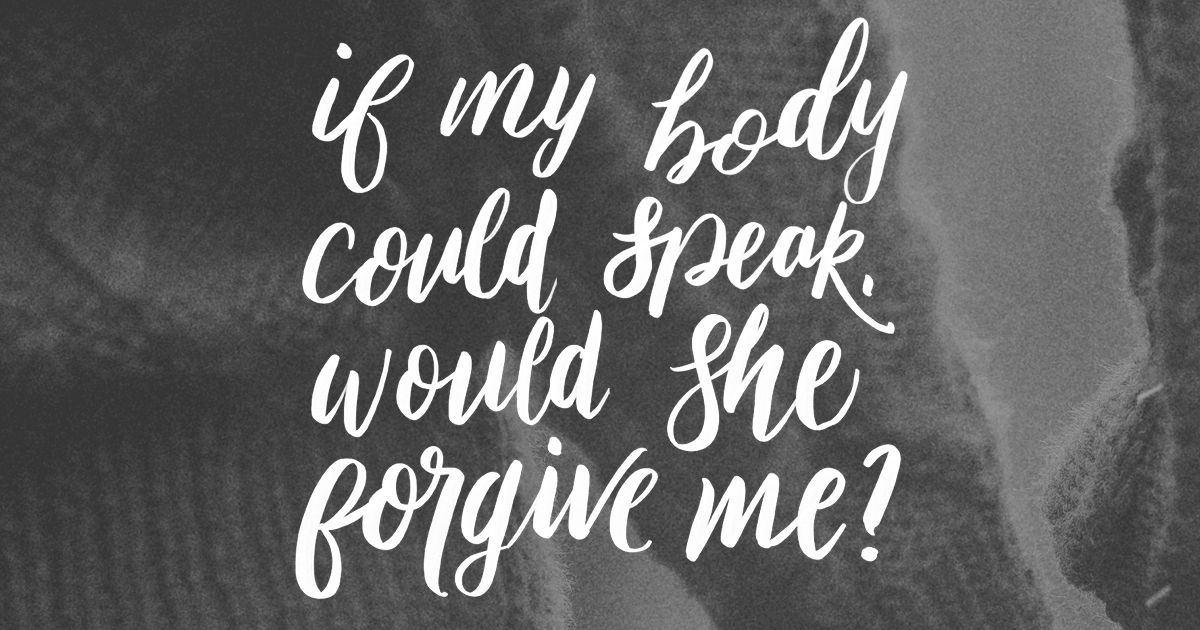

1. Personifying my body

Not long ago, a question bubbled to the surface of my brain: if my body could speak, would she forgive me? Though it sounds strange, it was wildly helpful for me to start thinking of my body as a being separated from myself. This mindset made it easier for me to be gentle and more forgiving with my body, because we are sadly often more willing to be unkind to ourselves than we are to someone else. I began to experience newfound guilt for putting my body through the abuse of my eating disorder, because what did my poor, loyal body do to deserve such violence? The answer is nothing, and the same is true for you, too: your sweet body did nothing to deserve to endure the wrath of you.

2. Setting attainable and realistic goals

When I was trying to quit smoking, I called my dad (an ex-smoker) and asked him for advice. “Don’t tell yourself you’re never going to have another cigarette again,” he told me. “Tell yourself you’re not going to have a cigarette today. Eventually, the todays will start to add up.” I applied some of this same logic to my recovery process. I found that if I tried setting the goal of never skipping a meal again, I inevitably failed because the goal seemed too lofty to possibly fathom. However, when I started telling myself that I wouldn’t starve myself that day, each day became a more digestible mini-task.

3. Considering that healing is political

Part of my main motivation to attempt to divorce myself from my eating disorder came from the knowledge that one of my greatest goals in life is to help raise future generations of strong and confident young women. How can I set a positive example for youth if I’m too preoccupied starving myself? A poem called “Ana” by Sierra DeMulder has a line that states, “To the mothers of Hollywood, the red carpet, and the ten pounds the camera adds: how will your daughter ever learn to love her body if she is forced to watch you wring out yours?” This line deeply spoke to me. In the mirror, when I’m struggling, some days I still remind myself: You cannot change the world on an empty stomach.

4. Remembering that “Fat” and “Skinny” are neither insults nor compliments

For so long, I was afraid to attempt recovery because I was terrified of getting fat again due to my history with childhood obesity. I had internalized the false and detrimental idea that “skinny” is the highest compliment one could receive. Conversely, I internalized the equally untrue and detrimental idea that “fat” is an insult. I now understand that “fat” and “skinny” are nothing more than physical observations—there is no value of personal worth attached to them. Once I was able to stop fearing fatness, I was able to (for the most part) stop putting thinness on a pedestal.

5. Picturing myself as a child

When I asked my mentor for help with navigating the angry, belittling voice that had set up camp in my skull, she invited me to picture myself as a child. “Think of yourself in elementary school. Think of what your favorite color or your favorite book was. Think of what holiday you were most excited for. Think of what brought you joy,” she instructed. I thought of the little girl I used to be, dressed head-to-toe in neon lime green, cupping the air with her hands in the backyard after dark, trying to catch a firefly. In my recovery, it is helpful to think of this little girl; how she still lives in an era inside of me. When I am tempted to go back to my old bad habits, I think of the life this precious little girl deserves to live. I try to understand that her and I are the same person. Doing so makes it easier for me to treat my current self with the same softness that I am willing to treat my younger self with.

Yves

Brilliant. And inspiring.

Thank you for this post and sharing

Hermione

Thank you, that was really helpful.

Thank you for sharing your tips!