“You have to work twice as hard to be half as good.”

These words, direct and uncompromising, are often one of the first lessons parents of color teach their children about how to exist in the world. One simple sentence contains multitudes of intergenerational trauma rooted in racism, sexism, xenophobia, and other forms of prejudice. As a child of first-generation immigrant parents, these words were more than a truism, they were a mantra.

I watched my mother constantly have to prove parts of herself to others—her education, her kindness, her very humanity—based solely on the color of her skin and the fact that she wears a hijab. I saw my stepfather work long hours in a pizzeria as he put himself through college and eventually graduated with an engineering degree, only to continue to face racism in his healthcare workplace due to his accent and heritage.

My parents were living embodiments of the narrative of the hardworking, self-sacrificing immigrants who provide everything for their children while assimilating and contributing positively to their new country. Yet, their success was still not enough to be fully accepted in American society or receive all the opportunities and privileges afforded to their white colleagues. Through observing and learning from them, I internalized the lesson that success demanded perfection, and it still might not be enough.

“You have to work twice as hard to be half as good.”

It was unacceptable to get less than an A in my classes.

It was unacceptable to be untidy or unmannered in public.

It was unacceptable to be idle. Time must be spent productively and ideally in pursuit of forwarding my education.

As I grew older, this lesson transformed into a core belief. I believed that I had to be perfect, that my identity and self-worth were defined by my academic and professional achievements. I believed that I was not entitled to or deserving of rest. I believed that it was not all right for me to just be, I had to always do.

The pressure, real and imagined, that I began to place on myself resulted in unrelenting anxiety that plagued my adolescence and early adulthood. I developed insomnia due to overthinking and worrying about all the expectations I placed on myself, translating to rushed mornings, running late to school and work, and intense fatigue throughout the day. Despite being a straight-A student for my entire life, I lived in constant fear of receiving a low grade in college and would spend sleepless nights studying for exams and revising already completed essays until my body was shaking from exhaustion. If I made a mistake or stumbled on a word in a presentation, I would internally berate myself until a panic attack ensued.

I survived like this for years until I became aware that my anxiety was out of hand and I needed to make a change. I had taken pride in being an overachiever throughout my childhood, which was reinforced by the pride my immigrant parents held in my achievements. It took going to therapy to unlearn the beliefs that had fueled my drive for perfection for so long. I am still unlearning and learning.

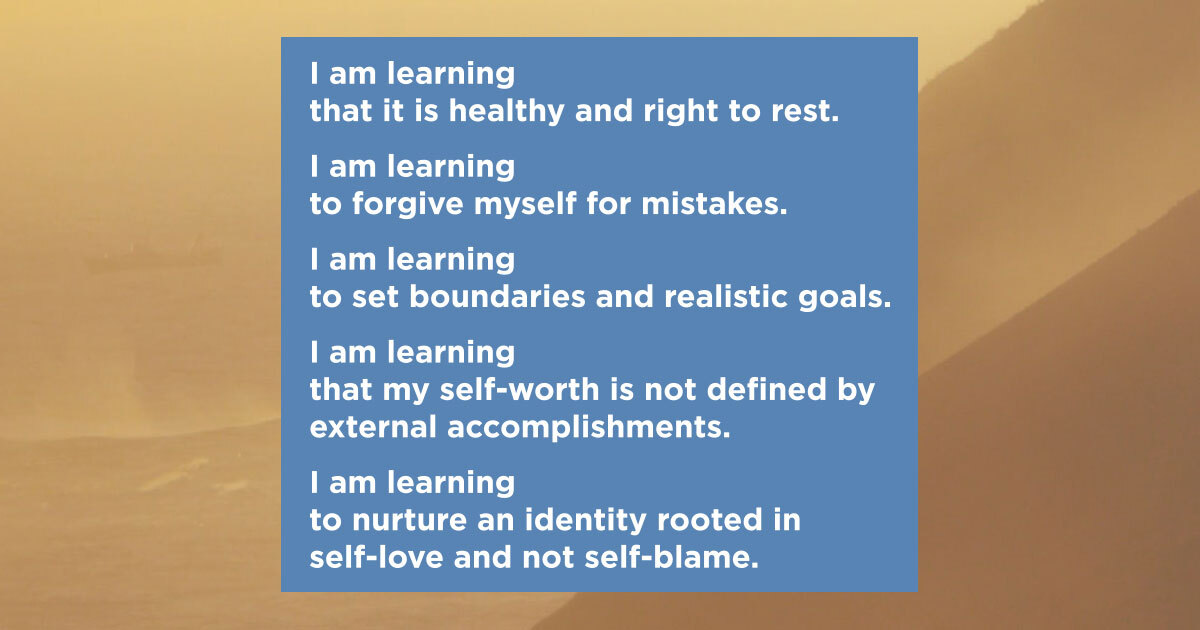

I am learning that it is healthy and right to rest.

I am learning to forgive myself for mistakes.

I am learning to set boundaries and realistic goals.

I am learning that my self-worth is not defined by external accomplishments.

I am learning to nurture an identity rooted in self-love and not self-blame.

Now that I work in the mental health field as a children’s therapist, I have reflected a lot on this lesson that parents of color and immigrant parents often instill in their kids. I believe that it is taught and modeled, with the best intentions, as a tool to prepare children to have a fighting chance in an unfair world that will devalue them for their race, ethnicity, color, and gender. Yet, rather than empowering us, these mentalities can often paralyze us with a fear of failure that manifests as anxiety and panic as we grow older. An unfortunate correlating factor is that many immigrant families do not engage in mental health care due to cultural stigma and lack of resources, funds, or information.

The tools I was given by my immigrant parents—a strong work ethic, resilience, perseverance, and determination—are important, but I know now that they must be accompanied by tools to simultaneously promote mental health and self-care. Otherwise, we deplete our spirits and become resigned to suffering and surviving, not thriving. We must promote mental health in families of color so that we, the children and descendants of immigrants, can thrive in all aspects of our lives, heal from intergenerational trauma, and achieve our highest goals and ambitions without barriers—which is, after all, the true immigrant dream.

You are not your thoughts. Anxiety is not who you are—you deserve to know peace. We encourage you to use TWLOHA’s FIND HELP Tool to locate professional help and to read more stories like this one here. If you reside outside of the US, please browse our growing International Resources database. You can also text TWLOHA to 741741 to be connected for free, 24/7 to a trained Crisis Text Line counselor. If it’s encouragement or a listening ear that you need, email our team at [email protected].

Eileen

Thank you for your story. I suffer from heavy anxiety. I came from a broken home and was told my Mother’s children would never amount to anything. I have 3 siblings and we all put ourselves thru college. One sister is a biochemist, teacher, social worker and artist. She went to school for all of these things. My other sister when to college for criminal justice and is now a mortgage broker. My brother had dyslexia, hyperactivity. He is a CNC machinist and a Microsoft programmer. So proud of my brother’s accomplishments. I put myself thru college to be a clinical medical assistant. After 5 years in the field. I left. I am an administrative assistant and customer service specialist. We all amount to be someone we are proud to be.