This piece was originally published on Medium here.

“How did they die?” It’s a natural question that we ask or think about reflexively when we hear about an unexpected death.

It’s the question I asked in utter anguish the night my son died, suddenly, July 27, 2019.

I’ve spent the better part of the last 9 months focusing on how my son died… by suicide. I’ve shared my story, written and talked about him, and I’ve shared my experience with this deep, abiding, soul-crushing, somehow endless, sea of grief and loss. Thousands of people know how my son died.

I am fine with people knowing how he died. I want people to know that suicide happens to families like mine and that it’s tragic and awful. I want everyone to know that even someone as vibrant and wonderful as my son Ben can lose their battle with mental illness. I believe that we should talk about it and tell the stories of the people we lose to it. The more we shine a light on it, the more we make it okay for people to express that they are not okay.

The Rest of the Story

But shouldn’t the rest of his story matter? The thought has flickered a few times, among the waves of sadness and loss as I’ve told our story… How many people know how Ben lived? How many people would even care how he lived? Then I wonder, is this a question everyone who’s grieving asks, or is it only a question we ask if we lost someone to suicide? Am I alone in asking myself that?

Do memories of someone we lost only ever matter to the family left behind? Our memories of Ben matter to us; we lived them, and we loved him. But do they really matter to anyone else? When I hear that someone died, after that reflexive “How did they die?” moment, I inevitably think of the deceased one’s mother or spouse or children… because I’m a mother, and a wife, and a daughter.

That’s what we do, right? As we try to understand, to connect, to possibly empathize in any way, it’s human nature to try and relate the experiences of others through our own lens by identifying and imagining how we might feel. “How tragic for his poor parents.” “How awful for the husband.” We look at the family left behind and shake our heads; we can’t imagine how we would be able to go on. How will they move forward from their horrific loss?

Then we try to figure out what words of comfort we can give, and we struggle. It’s even more difficult when we are trying to comfort someone we know because the stakes are so high. We’re afraid of causing more pain, so we think it’s better to simply say nothing. We revert to silence; after all, what does one say in a time like that?

And it’s further complicated when they died by suicide. A loss to suicide is so hard to talk about, to know about, to wrap our heads around. It’s icky and uncomfortable, and we don’t know what to say or do. Before Ben died, I didn’t know what to say to someone who suffered such a loss, so I would simply say, “I’m so sorry.” That never seemed like enough, but I didn’t know what else to say, so most often I would retreat. Now that I’ve experienced such a loss, I can definitively confirm: there really aren’t any words for this kind of loss. But I can also tell you firsthand, “I’m so sorry” is fine to say, as is “I don’t have the words for this,” which is honest, and genuine, and comforting in its simplicity.

There’s often a moment, immediately after someone dies, when we offer sympathy. We bring food; we say we’re sorry.

But after the initial shock, after the funeral and the moments where we gather and comfort and say goodbye, then what? Silence may seem the safest bet to us. We think, maybe they don’t want to talk about it. Maybe it’s too painful. I get it; I thought that too. I used to retreat to silence too.

But that doesn’t mean silence is the right action. Talking about Ben helps me keep his memory alive. He lived, and he was loved, and that should count for something.

We want to be there for our friends and loved ones. We want to help. So we tell them, “I’m here if you want to talk.” We might send a note or a card, but out of fear of hurting them, we step back. And then, we wait, feeling we’ve done our duty to our friend. If they want to talk, they can call us anytime. We know we’ve given them the opening, and we mean the offer in all sincerity.

But when you’re the one with the grief, the one who’s lost a loved one, that’s just too big of an opening. Talk about what? It’s too vague for me to begin to know how to respond. I’ve lost so many friends since Ben died; grief is so isolating. There are so many times I’ve wanted — times I’ve needed — to talk to someone, and I haven’t. It’s often too much effort to reach out, to call, to ask. I don’t want to be a burden, to be a drag on anyone’s time by asking to chat about my son.

Because just as you worry about causing me pain by asking about Ben, I worry about what you would think if I started talking about him. Do you really want to listen to my memories? Do you really care?

And then, as time moves on, we’re supposed to move on too. We’re supposed to get better, and people look at us with sadness when we don’t appear to make progress. I admit it, I thought so too. Before Ben died, I would see the occasional social media post about a milestone or a birthday or a simple, “I still miss you so much” or “I wish you were here,” and I would feel sad… and I would feel sorry for them that they were still grieving. It’s been months, right? Why is it still so raw? You must be struggling to heal if you’re still talking about your loved one.

And now, here I am, months later, still grieving. I figured it out: it’s never going to go away; I’ll never stop missing my son. But I’m learning to live with, and walk around, my grief.

A Weight to Time Conversion

I remember the funeral director telling me that Ben’s cremated remains would be about the same volume as a 5-pound sack of flour. I remember being so puzzled by it that I almost said it aloud. How can that be? He was 6 feet 2 inches, 185 pounds! I pondered that for hours in the back of my mind. It seemed so incongruous, so cosmically wrong, to reduce my tall, vibrant son to a volume of 5 pounds.

The number 5 still seems incredibly trivial and small. I want a bigger number than 5. My son was so much more in spirit, in intellect, in everything. His life, his presence, was much greater than a 5, of anything.

I realized that we measure lives in time. The oldest person in the world is tracked and noted. We celebrate birthdays to mark another calendar year. We talk about babies in weeks, then months, then years. My son lived slightly more than 23 years. That’s more than 5, but it’s still small. So, I did the math: 278 months and 27 (most of 28) days. In hours: 203,540 hours, give or take.

For someone who doesn’t much care for doing math, I do math a lot these days. I just did the calculations, and as I write this, it’s been more than 6,000 hours since Ben died. He lived for more than 200 thousand, so that’s around 3% of his life if I’m doing the math correctly. He would say that’s not a lot. Is that why it’s still so hard? It hasn’t been long enough, I guess. But will it ever be long enough?

Ben Thompson lived 12,212,460 minutes.

Before He Died… He Lived

Yes, my son was troubled. But he was brilliant and beautiful, and fierce, and he fought a mighty battle with mental illness. Then tragically, heartrendingly, devastatingly, we lost him, because he lost his battle.

But before he lost his battle… he lived.

Near the end of the movie The Last Samurai, the Japanese emperor Meiji asks, “Tell me how he died.” American Nathan Aldredge, who until that moment is the picture of brokenness, grief, and loss over his friend Katsumoto’s death, lifts his tear-filled gaze and says, “I will tell you how he lived.” At this moment, we see Aldredge mentally rising through his grief, realizing that if he tells the story of his friend’s life, Katsumoto’s honor and nobility will become the focus of his friend’s narrative.

When I tried to sum Ben’s life up in his obituary, I was told it was beautiful, but I kept thinking that there was so much more to say. An obituary is just a glimpse of the many minutes in a life. How could any obituary fully capture the essence of the person we lost?

What if we didn’t stop at the obituary? What if we made a practice to still give a grieving family the opening to talk — or not — but instead of just saying, “I’m here if you want to talk,” we gave them an invitation to remember, to share. What if we honored their loved one, their memories, and offered to help carry them?

What if we asked, Do you want to talk about him? And if they said yes, we asked, How did he live?

I Will Tell You How He Lived

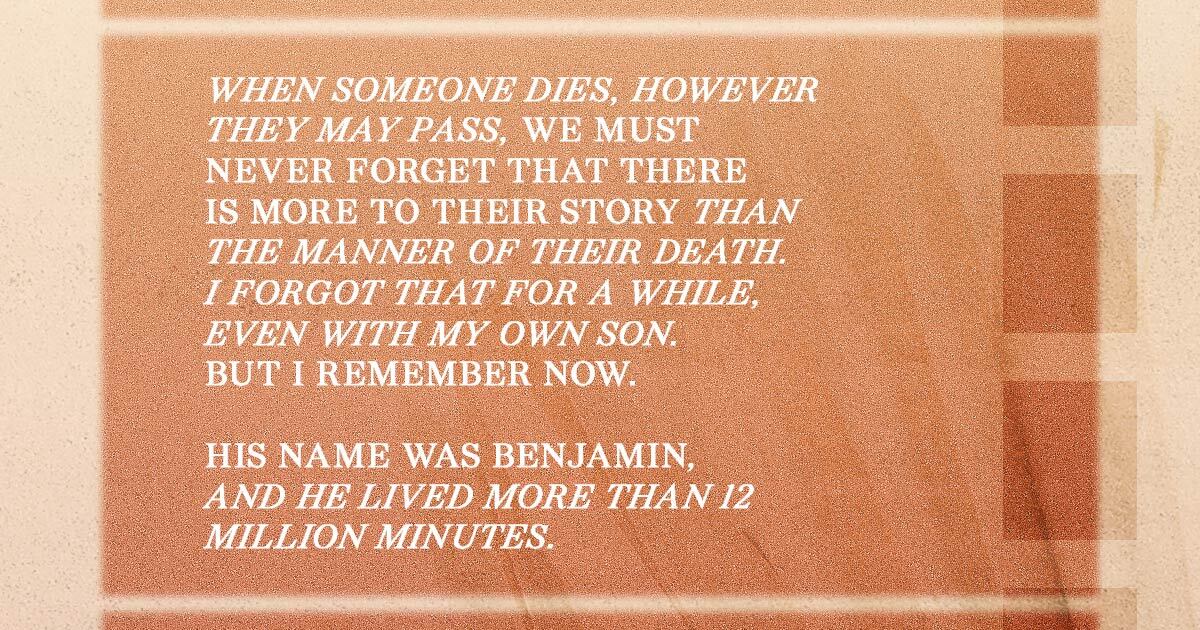

His name was Benjamin, and he lived more than 12 million minutes.

In his 12 million minutes, Ben had a family: a mom, a dad, a sister, and a brother who all loved him beyond measure. A family learning to step forward despite this horrific loss. A younger brother and an older sister who do not remember life before him. A family that is trying to hold onto the memories with him, and has only begun to make family memories without him.

What was he like as a child?

Ben cried 24–7 with acid reflux when he was just weeks old, and I held him in a rocking chair for hours. It was the only thing that soothed him, for months. He loathed tags in his shirts and seams in his socks; he found unexpected touches painful; brush his arm, and he would flinch visibly. His sensory processing problems were lifelong, and they were the root source of much of his anxiety. The world can be so hard when it is often painful at the point where it touches your skin.

You can’t know his childhood without knowing that Ben worshiped his oldest cousin for years when he was little. There were several summers at the Jersey Shore when he followed his cousin around, did whatever his cousin did, and ate whatever his cousin ate, even if at home he didn’t like it. We laughed at the time, but I remember thinking that kind of hero-worship only comes from a young child’s heart, and it would fade. While Ben did eventually make his own dinner choices, his love for his cousin — for all of his cousins — remained every bit as strong. His cousins loved him in return, and they were all there the day we said goodbye, holding Ben in their hearts while they held me, my husband, and our children in their arms.

I also remember how when he was four and learned to ride a bicycle without training wheels after two hours of trying, he suddenly yelled “watch this Mama!” and popped a wheelie down the driveway, grinning. I watched him, so awestruck that I forgot to fear he might fall. He never feared he would fall.

Ben could spin in circles, hundreds of times, and not get dizzy, not once, in his entire 12 million minutes. In fact, a wise elementary school teacher used to let him go out on the playground and spin on a tire swing if his anxiety started to overwhelm him. His body craved movement sometimes, and spinning made him feel better. He learned to snowboard, and jump, and spin, and do flips on a trampoline that used to terrify me.

Speaking of movement, Ben rarely stopped. He climbed a tree in a tux when he was the ring bearer for my brother’s wedding when he was 7; I have the picture to prove it. All I could think at the time was “That’s a rental, sweetheart!” but his laughter made me laugh too. My son could climb anything, from a young age. There’s a recent picture of him as an adult, perched in a tree. I think he liked looking down on the world.

Ask what they were like as a child. You will find out the promise they had, the wonder they possessed before the dark clouds took over, before the world taught them anything but love and hope and laughter.

What was he like in school?

Ben was brilliant at math. I’m a word girl; math isn’t my thing, and I took a long time to figure out he lived more than 12 million minutes; Ben would have gotten there in moments. He used to do math in his head for fun, and he always wondered why he had to show his work if he knew he was right. On long car rides, he was as likely to be entertained with random math problems made up in my head as any road trip game I could think of.

My son was brilliant at so many things. He loved engineering and studying how things worked. He loved physics because, to him, it was math. He wanted to use math and engineering and physics to solve big problems. His undergraduate research focused on the heat transfer of solar energy and he talked about how it could affect space travel and renewable resources someday by helping engineers understand how they could harness the sun’s energy better. One of his best friends from college told me “He was such a genius. He could learn anything.” He could, too. He was so capable and smart and people were in such awe of his intellect that it was easy to overlook the anxiety, self-doubt, and depression that lurked behind his beautiful green eyes.

School was so easy for Ben that, paradoxically, it was hard. A school psychologist once told us Ben was the brightest child he’d ever tested, at the same time he observed that school would never come easy for Ben. He was right: the easy stuff was just busy work for Ben and he hated it. He craved the challenge of the unknown and the uncertain; he wanted to figure things out. He spent so much of school feeling anxious because it couldn’t engage his thoughts enough. His handwriting was legendarily awful; his brain went so much faster than his hand that he just couldn’t keep up with the thoughts. As a result, he felt anxious a lot at school. I remember his fourth-grade teacher calling him a bundle of nerves and saying it hurt her heart that he was so anxious all the time. He seemed to improve through the years, but that anxiety never really went away; he just got better at hiding it from most of the world.

Ask what they were like in school. You might see glimpses of the person to come, the brilliance and the struggles and the triumphs. You see the person in progress and the inflection points and understand the foundation of the person they became.

Did he make you laugh?

Ben once saved enough money to buy a PlayStation II, all on his own, by collecting change. He cleaned up the neighbor’s yard for quarters and ransacked my car on a regular basis. He would regularly empty out the bucket and count it, carefully, and announce the latest tally. We didn’t pay a lot of attention, until the day he announced, triumphantly, that he had enough. I didn’t really believe him, but I dutifully took him, and the giant bucket, to the bank. It took two people to carry that bucket to the giant change counter in the back, and Ben stood, dancing with glee and triumph, as the sound of coins rattled, on and on, for an impossibly long time. The teller came out, her expression a mix of awe and pride, as she handed him the total. I don’t even remember how much it was, and I can’t remember if she was more impressed that he’d saved that much change, or that he had the amount exactly right. He was proud of himself, but he was more excited about getting the PlayStation. “You should save your money,” a kind elderly gentleman told Ben as he announced he was buying a game console. Ben stared at him, horrified, “But I already did! And it took me FOREVER!” The man laughed, and with a nod said, “I stand corrected. Good job, young man.” Ben was too excited to discuss it further and ran toward the exit. “Can we go to the store right now?”

One of his friends told me that Ben had an irresistible laugh. It’s true; we all loved his laugh because it made us laugh too. I came home one day to find him pulling a kayak out of the back seat of his car, grinning. He and his friends had been to the river and stuffed the kayak in the backseat with the ends sticking out the windows on both sides like some sort of automotive Viking helmet. “I got stopped for this setup,” he laughed, “but sometimes you just gotta kayak, Mom. Plus he gave us full marks for safety — I mean we put flags on it and everything” as he motioned to the red bandannas carefully tied to each end of the watercraft. “I guess next time we should add a WIDE LOAD sign.” I offered to help get the kayak out. He paused for a long moment, and shrugged, “Naah it’s fine.” I started toward the house. “Hey, could you help me make a sign though?” Ben recognized absurdity, even when he had a hand in creating it, and he could find the humor in anything.

Perhaps my favorite memory in the book of Ben happened just months before he died. We went to Florida for his cousin’s wedding, he and his sister and I. The trip was delightful, and sweet, and so very Ben. It started with him needing a belt, and a tie, both of which we borrowed, from two different family members. It progressed to laughter over his too-tight pants from his ill-fitting suit which made his dancing even more awkward. During the epic car ride with all of us giggling as he played with both the music and the temperature controls and declared himself “DJ Climate!” the adventure turned to snorts of laughter. It ended at the hotel with all of us exiting the car like a troupe of clowns, one after the other, to the astonishment of the valet. In the middle of it was Ben, full of life and joy and adventure. You had to be there to really understand it, but we had so much fun that this is how we all choose to remember him: carefree, laughing, filled with light.

Ask if they made us laugh. We cling to those memories, the moments of joy and laughter, the times we had when we didn’t know how many minutes more we had with our lost one and their joy was contagious. You’ll get a glimpse of why we love them and why it hurts so much to lose them.

Did he ever get hurt?

I remember his broken elbow from doing back-flips off a bed and missing the landing, and his broken arm from snowboarding and catching an edge learning a trick in the skate park. He incurred an epic road rash from skateboarding down College Hill Road (a road as steep as it sounds) and crashing, hard. The accidents only slowed him down though; they never stopped him trying the next trick or wanting to go faster. I remember his first fender bender when he clipped someone on the highway, and then called me from the car to tell me in a trembling voice that the people he clipped were screaming at him and he was afraid.

I remember the many times his heart was broken or his spirit damaged. The times he called me to tell me he’d broken up with his girlfriend or lost a friend to suicide or an overdose. The times I sat on the phone, listening to his tears, wanting to fix it, knowing that I couldn’t, and worrying that he couldn’t either.

Ask if they ever got hurt. You’ll begin to see glimpses of the damage left by growing up, by opening your heart to others, by being willing to love and be loved, and thus risk being hurt.

Did he ever scare or anger you?

Ben could “disappear” for days at a time, going radio silent, which often worried me. I knew his struggle with anxiety and depression, even if most people never saw it. I also knew that Ben evidenced signs of a bipolar mood disorder. He talked to me about it and expressed his concern about himself. The year before he died, he had even sought an evaluation. But he was wait-listed, and then his college course load took over, and the topic was dropped. I knew, though, that part of the avoidance was that he was afraid of it. There was a thought that he couldn’t express, but which I understood: I’ll be like you, mom. I’m afraid. He knew it could be a struggle, but that it could be overcome and managed; I showed him by example. Still, he also knew that it can be big and scary because there were times when, living with me, it was. It just was.

I remember my broken heart the first time he ever said “I hate you Mom!” and meant it, much to both of our terror and sadness. We both cried, and then we hugged. I remember the sneaking out and the yelling and the profanity-laden text messages and battles over his decisions in high school, when he smoked pot and partied and was defiant. We worried about both his safety and our sanity, and our interactions were as likely to end in anger and yelling as love and laughter. His life was not perfect, and neither was our relationship.

We figured it out, though. There were brushes with law enforcement, but we all survived, and we all learned. He learned we were in his corner, and that we always had been. We learned to choose our battles better and recognized that his behavior had always been more about trying to manage his intense feelings and slow down his brain than it was about defiance.

We learned to be better with each other, to attribute good intentions, and our estranged, angry son became a loving, adult one. Our text message interactions turned from spiteful diatribes to long, drawn-out discussions of philosophy and dreams and advice, political rants, and hopes for the future. I have them all saved. They are a record of a relationship broken, then tentatively mended, then strong.

Ask about their imperfections. Because no loved one is ever perfect, ask about the imperfections. You will likely learn that people can make mistakes and overcome them. You will learn that we can be honest about who we lost and still love them. Give us space to remember the whole person. That’s truth, which is always easier to remember and lighter to carry.

What brought him joy?

Ben loved good food and good beer. The lobster and truffle mac and cheese at Timber Restaurant in Bangor, Maine made Ben tearful with joy the first time he ate it. Maybe it was just that he was a hungry college student, but when his aunt suggested he order a second bowl, he did. Our server brought him extra bread because she was so amused by his unabashed adoration for that bowl of mac n cheese. He introduced me to Black Bear and to Marsh Island beer, and we laughed over him deciding to live just down the street from two really good breweries as if the proximity made up for the horrible, ramshackle, college-student-on-a-tight-budget, dive of a house he lived in. “Location, Location, Location,” he quipped.

He loved hiking, camping, and swimming. Being outside, on a mountain, on a slope or on a trail, on a lake, in the river, or sitting around a campfire were his jam. He once hiked Mt. Katahdin, including the notorious Knife Edge trail, in Vans and flip-flops, carrying a tent on his shoulder. He told me once that he felt most himself, most comfortable in his skin, when he was outside, where there is always peace, and light and love, and breath. That may well be the most important lesson he ever taught me.

Ben’s academic success brought him joy. He pulled the highest GPA of his entire academic career as a senior while taking an unheard-of 24 credits. He never wanted or expected accolades, but when they came, his surprise and delight reflected the essence of his person. Never one to flaunt his intelligence, he found the recognition of his hard work, at last, to be incredibly satisfying.

He loved to learn, and he loved complexity. Ben’s research project for his senior capstone required creating his own testing apparatus and learning a calibration machine he’d never worked with before — and that no one in his lab had either. So, he taught himself to use it from the manual, which he carried around with him for weeks. The more complicated the topic, the more excited he was to learn about it.

Ben presented a carefree face to the world, and much of the time, he was. His car, his computer, and some of his clothes were held together with duct tape. As long as they still worked, even at the minimum, he was fine with it. He didn’t need or even want new; he just needed functional.

Ben tried so hard to tread lightly on this Earth, to care for his friends and the natural world he loved so deeply. Of all the things that made him happy, helping his friends and hanging out with them brought Ben the most joy. He would drop everything to help a friend, no matter how far away, no matter what favor. I believe one of the reasons he lost his battle with his illness was that he was trying so hard not to burden his friends or his family with his own struggles.

He gave freely of his time, his talent, and his meager treasure to his friends and those he cared about. He loved and laughed and touched so many hearts and minds. He was brilliant and beautiful and funny. One of his friends told me recently that his laugh is one of the things she misses most. I miss that too, and I miss his smile, and I miss our late-night texting marathons. I miss my son, and I miss my friend.

Ask what brought them joy. You will let us share the essence of the person they were; what they valued, what they leave behind, and what the world lost — what we lost — when they left it.

I Will Remember How He Lived

There is a song by the band Dispatch, “Only the Wild Ones,” that I play a lot these days. It makes me think of my son, my beloved son who loved adventures and made us all love them too, who could make an adventure out of almost any experience:

Only the wild ones /Give you something and never want it back / Oh the riot and the rush of the warm night air / Only the wild ones / Are the ones you can never catch / Stars are up now no place to go, but everywhere

When someone dies, however they may pass, we must never forget that there is more to their story than the manner of their death. I forgot that for a while, even with my own son. But I remember now.

His name was Ben.

He lived more than 12 million minutes.

He was loved.

I will remember how he lived.

Whatever you are facing, there is always hope. And we will hold on to hope until you’re able to grasp it yourself. If you’re thinking about suicide, we encourage you to use TWLOHA’s FIND HELP Tool to locate professional help and to read more stories like this one here. If you reside outside of the US, please browse our growing International Resources database. You can also text TWLOHA to 741741 to be connected for free, 24/7 to a trained Crisis Text Line counselor.

Jamie Dee Milano

I am grateful for this beautiful memoir and glad that I read it to the end. It has strengthened me and I hope you, as well. Thank you.

El

Hate to ask .. how did he pass and what were the final moments ?

Lisa Johnson

I resonate with your story of your son Ben. I have a similar story with my son Connor who also died by suicide the day after his 25th birthday. Your transparency about the great memories and the hard stuff too was so good for me to read even though I did it with some joy and some tears. But isn’t that the truth of looking back over most anyone’s life? We all have good and bad and that’s what makes us appreciate the sweet times like you do with Ben. You made some great points and I hope many will read and take to heart. Keep sharing your story!!

Cindy

Thx for this story. Today I will write my husbands story and I will tell everyone how he lived.

Alisha Eggleton

My little brother of 28, his name was Benn. Your memoir resonates closely in ways to my family and our semi-recent loss of him. Thank you for the hope and courage of your story.

Melissa Kennedy

My child Declan (Lauren) lived almost 14.5 million minutes . They lived showing more kindness to everyone in their 27 years than most people ever will. I am broken and devastated and still find it nearly impossible to see life continuing with out them. I get up and hope to make it through each day and be there for my husband and my other children. Reading your story about how Ben lived to try to do this more with my child. And to maybe ask other people to talk with me or just listen so I can remember the living not how they died.

Kim Meredith Holmes

What a beautiful memorial and tribute.

Wendy

This speaks volumes to me. I am also a mother who lost a child to suicide. She was 15 and her lifeless body was still warm when I found her and gave CPR til the paramedics showed up and took over. 2 hours they worked on her while my house filled with family, friends and countless police officers. She died about 30 mins before I woke up and found her. I too died that day. The Wendy who went to sleep that Saturday night is gone, and I truly believe I’ll never be that girl again. I lost my job and my relationship went up in flames soon after. And sure enough, all those that rushed to my side with casseroles, overwhelming sympathy and of course empty promises to be there no matter what start dropping like flies. By the time the denial fades and I truly start to feel the reality of my family’s unfathomable loss, those promises had expired. I lost my baby, and my will to live. 3 years later I still see her face everytime I blink and honestly I hope that never changes. My favorite topic is Mara. I long to tell her story, the good and the bad so I can keep her memory alive in the only way I know how. But her story and my desperate attempts to open up to someone… anyone, falp on deaf ears. Ive alienated everyone I love by my sadness because it makes them feel uneasy. Reading your similar story brings me just enough relief to keep going and for that I thank you.

Relista Dilosa

Thank you

Leyla Sanai

I’m so sorry. I was 21 when my sister killed herself. She was 22. I will never know exactly why., although she was troubled and had turned to hard drugs. Intractable depression is a terrible thing, especially in someone who will not seek help or consider taking medication, but will take all sorts of recreational drugs which may exacerbate the mood disturbance.

I’m a retired hospital consultant, by the sounds of it older than you because I qualified in 1989. I worked as a physician and then an intensivist and then a consultant anaesthetist. Since the year 2000 I have been a patient hundreds of times and had over 50 operations and procedures in the NHS.

This is a beautiful piece and your love for your son shines. The grief does last forever, but it dulls to a vague throb that will sometimes overwhelm you but will allow you to experience joy with other people you love. I’m glad you have other children.

With my very best wishes.