Note: This piece talks about suicide, suicide ideation, and self-harm.

I was 11 years old, doing homework when the thought came into my mind: If I don’t finish my homework by 7:30, I should kill myself.

What started as an alarming intrusive thought continued to grow and change from scary to something I felt was inevitable as it was left untreated for the next 15 years. As I’ve gone through the years of denial, suppressing, and now finally addressing these thoughts, I’ve been met with a host of various opinions on my suicidality. I’ve believed in misinformation, hidden things instead of being open about them, and survived numerous attempts while trying to get myself the help that I needed. Through my lived experience as someone with chronic suicidality, I’d like to present you with some common myths about suicide, and what the actual truth is.

Myth 1: Talking about suicide or asking someone if they are considering suicide will increase the likelihood of suicide

My first hospitalization in order to keep me safe from a planned suicide attempt happened in 2020. When I returned home, I decided that I was going to talk about it, rather than let myself be embarrassed about what was really a good decision that kept me alive. I took to Facebook to share. It wasn’t long before I received a well-intentioned but misinformed message saying that by talking about suicide, I might push others to do it or make someone consider suicide who previously hadn’t.

However, the opposite is true. Not talking about suicide creates a belief that those experiencing suicidal ideation (SI) cannot talk about it due to fear and stigma. Allowing space for someone to speak about their struggles gives them the opportunity to get help and consider other options.

Myth 2: People who talk about suicide are doing it for attention

Shortly following my first hospitalization, I met with a therapist associated with the hospital. I sat down in his office, knowing that he’d read my medical file, which stated my clear plan and intent for suicide, and that my outpatient therapist had recognized the warning signs and helped me get into a hospital in order to provide safety. Imagine my surprise when he looked at me and said, “Well, if you were actually suicidal, you would have just done it.”

There are a lot of problems with this myth. The first is the negative connotation associated with the word “attention.” When used in this context, it’s meant to undermine the legitimacy of someone’s feelings. They aren’t actually in the intense pain that often causes suicidal thoughts, they just want someone to pay attention to them. Honestly, attention is not a bad word. If you think about it, when someone has an injury, you would say they need medical attention. SI isn’t any different. It cannot be treated unless attention is brought to it. If someone says they’re suicidal, they should be believed. And even if it turns out that they didn’t actively want to kill themselves, validating and understanding what they’re going through can keep those thoughts from going from passive to active and assist them in finding the help they need.

Myth 3: Suicide is selfish, weak, and cowardly

A few months ago my mood was at an all-time low. I was constantly assessing the people around me for signs that I was becoming a burden. My brain had me convinced that I was too much and all I did was drag everyone around me down. In the overwhelming guilt that I felt, I decided suicide was the best option, not for me, but for everyone who was trying to help me. This is a common thought that people who attempt or consider suicide have. They, like me, can become completely convinced that ending their life is better for everyone. It’s not a selfish thought.

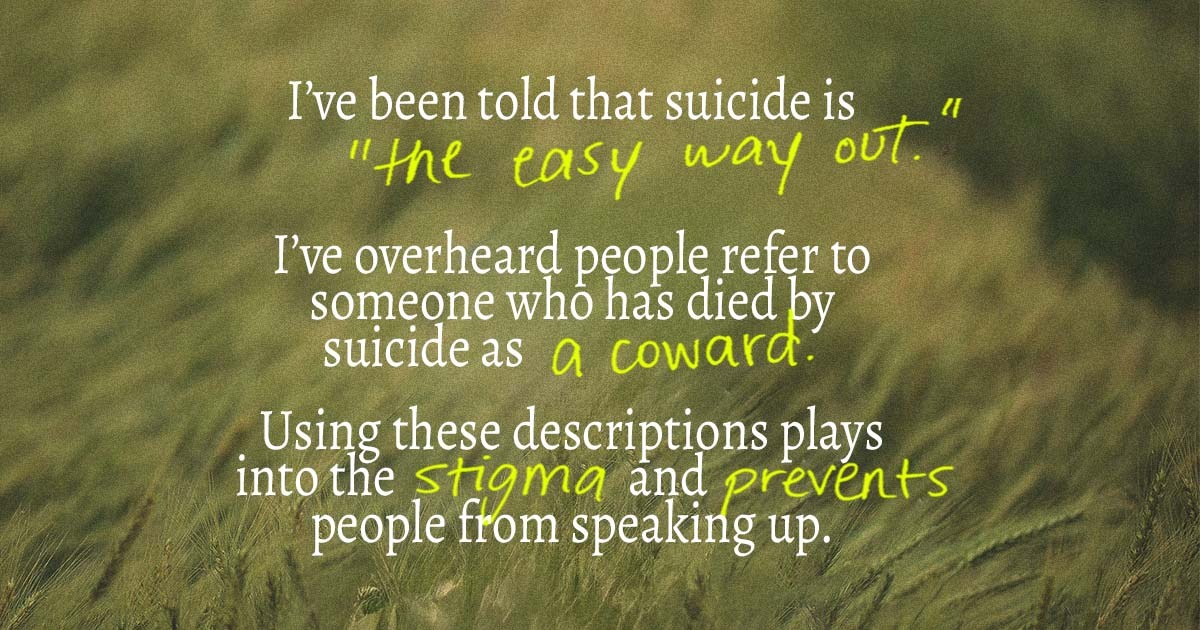

I’ve been told that suicide is “the easy way out.” I’ve overheard people refer to someone who has died by suicide as a coward. Using these descriptions plays into the stigma and prevents people from speaking up. The truth is that suicide is often the result of immense pain, physical or emotional, intense trauma, or an underlying mental health condition.

Myth 4: Suicide happens suddenly, without warning

In high school, I was self-harming, which was often visible, though I tried to hide it. I was also a writer. I wrote poems for our school newspaper. I wrote short stories for various writing contests. A theme throughout almost all of my writings was some level of depression and a lot of analogies for suicide. I can remember as far back as 5th grade writing a story in which the main character was rescued and given a purpose just before a suicide attempt. I had long periods where I withdrew from friends and spent a lot of time thinking about how I could end my life.

Many suicides are accompanied by warning signs. Sometimes they’re subtle, sometimes they seem so obvious in retrospect that it hurts. Social withdrawal, increased drug or alcohol use, and talking about a desire to die directly or indirectly (wishing they wouldn’t wake up, wishing they’d disappear) are a few that can indicate the start of suicidal thoughts or planning. Other signs such as giving away possessions, saying goodbyes, or gaining access to lethal means typically precede an attempt. Sometimes, a person will go through a period of being socially withdrawn and depressed, followed by a sudden change of mood where they appear calm and “fine.” As confusing as this is, that is sometimes a sign that a person has finalized a suicide plan, and the change in mood is caused by them believing that their pain is going to end.

Myth 5: Talk therapy and medication won’t help

At the beginning of this post, I talked about how I left my suicidal thoughts untreated for 15 years. Growing up, mental health wasn’t real. It wasn’t talked about, treated, or even just acknowledged. I suffered a lot more because of this.

Five years ago I started the search for a therapist as I realized the thoughts were getting worse and I could no longer suppress them. This is how I learned the importance of finding a therapist who is a good fit for you. I met with two and left both feeling worse. At that point, I probably would have agreed with this myth. Therapy and medication thus far weren’t helping. But I continued my search, until two and a half years ago I found my current therapist and everything clicked. I was believed and validated. I was hospitalized—which made me feel so much more comfortable because I knew I was being taken seriously—and I began the journey of finding the right medications.

It’s been a long two-and-a-half years filled with more hospitalizations and more medication trials than I can count. However, it has helped. I’m not cured. There’s no magical, quick fix. But I can say with one hundred percent certainty that if I had not found my therapist and hadn’t gotten on medications, I would not be writing these words.

The author talks about their experience with suicide and mental health advocacy on YouTube. You can check out Mel’s channel here.

Our Suicide Prevention Campaign is all about providing tangible hope. Giving people something they can hold on to and making sure they know that when they need help, resources and support will be there. Throughout the month and around the world, people show up to share their stories and raise $300,000 in crucial funds for our Treatment + Recovery Scholarship Program and FIND HELP Tool. We could not do this work without the collective effort and determination of folks across the globe. Suicide affects everyone, and this is a fight we are in together.

For more information about this year’s campaign and how you can get involved, head here.

Whatever you are facing, there is always hope. And we will hold on to hope until you’re able to grasp it yourself. If you’re thinking about suicide, we encourage you to use TWLOHA’s FIND HELP Tool to locate professional help and to read more stories like this one here. If you reside outside of the US, please browse our growing International Resources database. You can also text TWLOHA to 741741 to be connected for free, 24/7 to a trained Crisis Text Line counselor.

Cathy

When someone has serious mental illness, voices can become so intrusive, that sucide can appear to have no warning signs. When the stigma of asking a person about suicide, can impede get help early.