This post discusses the topics of suicidal ideation and suicide in detail. Use your discretion.

“So, do you want to tell me a bit more about those intrusive thoughts you mentioned? You said it felt like your brain was yelling at you.”

I sat on my bed with my heated blanket wrapped around me, holding my phone out. On the screen was my new therapist. We were having our first appointment via telehealth. Already, I was enjoying his vibes—he was easy to talk to and seemed to have the same deadpan sense of humor I did when it came to darker topics.

I readjusted, tucking my legs beneath myself in a reflexively defensive pose. “Yeah, of course,” I responded before elaborating.

“The first one I can remember clearly, like the first time I had an intrusive thought and really identified it as an ‘other’ was when I was 16 or 17. I had just gotten into a fight with my first boyfriend and was driving home, and it’s all curvy back roads. I remember going around this really sharp bend and my brain just started screaming at me to drive into a tree. ‘No one can be mad at you if you’re dead’, it would say. ‘Stop all the pain, floor it.’ It terrified me to be having these thoughts. I didn’t know where they were coming from. But I also knew it wasn’t just a one-off instance of my brain being funky. I had been miserable, out of it, numb, vulnerable, for months. It was like the emotions I was trying to ignore were bursting out of my brain and screaming.”

That’s how it started.

Fast forward two years, and I was a freshman in college. My depression was at an all-time high (low?) and the thoughts were nearing constant. Every little thing I did was criticized by my own mind. It told me I couldn’t do anything right as I sank deeper into a rapidly darkening place. In school, I was struggling, and my personal life wasn’t any better. My relationship was fizzling out (in large part thanks to symptoms of depression and a lack of understanding on the part of my partner) and I was having trouble making new friendships on campus. During this time, my anxiety spiked to the point of intense daily nausea. In turn, my brain told me I was wasting food, energy, and money by eating—only to throw it up again later. I listened to the little voice, and I stopped eating. I was lucky if I had a cheese stick a day to keep me upright.

Still, I couldn’t do anything right and knew I needed help.

I spent days building up the courage to call my campus’ resource center, so anxious and convinced they’d dismiss my challenges as being unimportant. My brain continued with the harsh critiques, telling me I wasn’t worth the effort, even for someone getting paid to hear my problems. But eventually, I picked up the phone and started therapy in secret.

That first appointment was nothing short of terrifying. I was certain I was either going to be laughed out of the building or locked up. But some part of me, a small part, a quiet voice tucked away in a corner untouched by the darkness, whispered that I had to try. I held on to that voice like a lifeline, and, for the first time since they began two years prior, I spoke my intrusive thoughts aloud.

Even then, I knew the thoughts were illogical—they had to be—but it didn’t make them feel any less true.

My first therapist nodded slowly, taking it all in. “Have you heard of the Call of the Void?” she asked.

I had, briefly. Essentially, the Call of the Void is a natural human phenomenon where we sometimes have intrusive thoughts about dying; oftentimes we are the agents of action, causing our own deaths. It is thought that this phenomenon is caused by our natural human curiosity for what comes “after” life.

“I think that’s a small part of what you’re feeling here.” A gut punch. My brain was right after all: my issues were unimportant and I was stupid for thinking otherwise—

“But, I also think it’s clear you’re struggling from depression and suicidal ideation.”

There it was. Words. Words I could use to describe what I was feeling, had been feeling for years. Validation. Confirmation that I was not all the horrible things my brain told me.

For the first time in my life, I knew what was going on with me, and the little voice, that speck of hope and light, glowed a little brighter. Maybe I could be fixed or cured…

I wish I could tell you that that moment was a turning point for my mental health, and while it was in many ways, it was not the end of my pain by any means.

I started going to therapy weekly and taking antidepressants. I was pushing myself to be more social and to eat at least one good meal and snack a day until my appetite returned. I reached out to all of my professors and asked for support. I opened up about my depression to my family and friends. I was doing everything right.

And then, I had a bad day. A really bad day.

The weeks of work I had put in, all the progress I had made, felt nonexistent that day. I can’t recall what happened or caused it, I just remember that I sank lower than I had in a long time—maybe ever.

It was on this day that I would do something my mind had kept telling me to do, but I never had the energy to do before: I stepped in front of traffic.

I don’t think I knew what I was doing. I don’t think I wanted to die in that moment. But after years and years of this persistent voice telling me to do it, to hurt myself, to stop the pain—it just happened. My body moved into the street. It was automatic. Self-destruct.

But the car stopped. And I ran. I ran and I ran, tears streaming down my face until I got back to the courtyard of my dorm building. Sobs racked my body as I realized what had happened. I called the suicide prevention hotline, barely able to choke out the words: “I don’t want to die. I don’t want to die. God, I just want the pain to stop. Please, I just want to live again.”

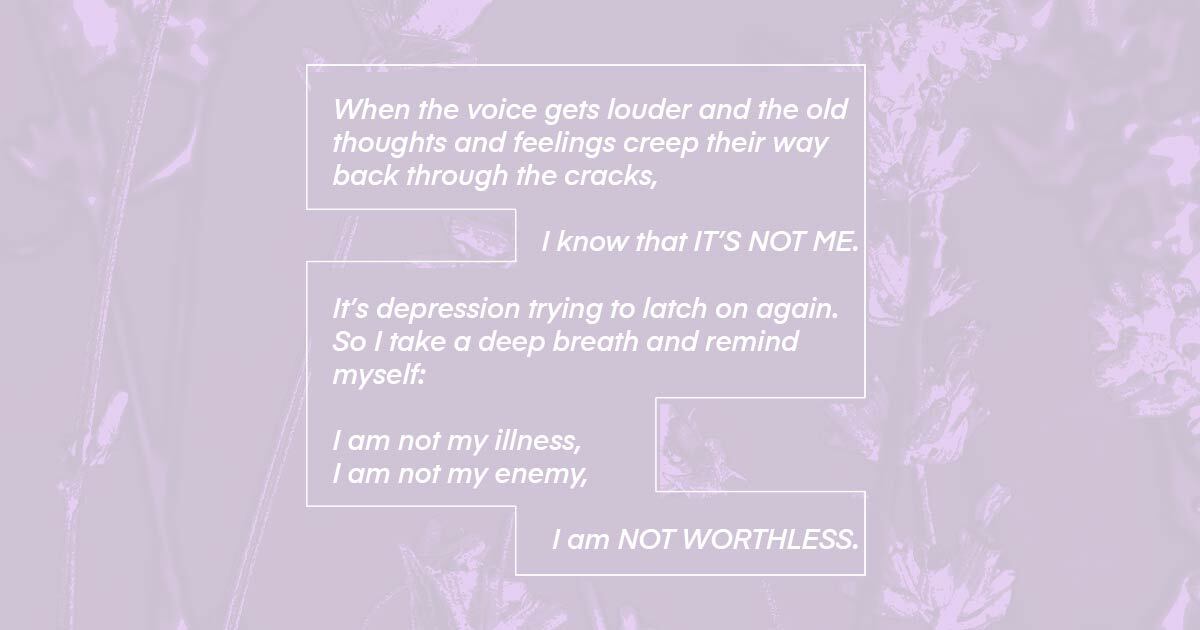

I’ve dealt with intrusive thoughts, suicidal ideation, and depression for much of my life. I can cope with it now and find ways to challenge and defy the voice in my head, but it doesn’t mean it’s any less scary to hear it shouting horrid things from the depths of your soul. I’m not sure if the weight of those thoughts has gotten any lighter, or if I’ve just gotten stronger from carrying them for all these years—but what I do know is that the big bad voice in the back of my brain doesn’t come out as often. The light, once tucked away in the corner, is now as expansive as a home. Even when the voice gets louder and the old thoughts and feelings creep their way back through the cracks, I know that it’s not me. It’s depression trying to latch on again.

So I take a deep breath and remind myself: I am not my illness, I am not my enemy, I am not worthless.

I recognize now that this voice is just that—a voice. I have my own voice, too, one that loves to sing off-key and laugh with friends and tell silly stories. I live in a world of billions of voices, and I get to choose which ones I listen to. Some may be louder than others, but that does not make them more important or more truthful; it simply makes them more annoying.

You are not your thoughts. Your thoughts do not define who you are. We encourage you to use TWLOHA’s FIND HELP Tool to locate professional help and to read more stories like this one here. If you reside outside of the US, please browse our growing International Resources database. You can also text TWLOHA to 741741 to be connected for free, 24/7 to a trained Crisis Text Line counselor. If it’s encouragement or a listening ear that you need, email our team at [email protected].

Karon

I can relate to so much of this. Thank you for sharing your story. It put into words some of what I’ve been living. I remember that feeling of knowing how close you came to dying. I’m so glad that you are still here. I’m so glad that I got to hear your story. I hope that one day, the light tucked away in a corner of my brain is as big and expansive as a home…a big, safe home. And I hope I can learn to live in that safe light.